The low road to economic ruin, as illustrated by a trip through Mozambique

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

By Greg Mills, Richard Harper and Mike du Toit• 25 April 2021

The road between Changara and Guro, Mozambique, (Greg Mills)

Our five-day journey across Mozambique reminded us of how little progress has been made in that country, of the cost of war, the extent of the carelessness of its political leadership, and of the relative impotence of donors to enable development.

“You go to the police station,” menaced Sergeant Silvestre, turning to point behind his back at a lime-green building, explaining that the crime was “not wearing a mask in the car”. We were stopped in a queue of trucks and cars negotiating speedbumps, army, police, paramilitary, immigration agents and sellers of nuts, cooldrinks and much else at the bridge that spans the great Save River in Mozambique’s Inhambane Province, just north of the popular tourist destination of Vilanculos.

We saw no tourists at all on the road to Malawi from Maputo, not even adventuresome overlanders and members of the 4×4 brigade. This may have (partly) been down to Covid-19, but their absence was hardly surprising given the levels of intimidation and friction from officialdom.

We had set off from Johannesburg two days earlier, a short (and, as it turned out, a fast and friction-free) 550km day’s driving to Maputo. But the Lebombo/Ressano Garcia border post just 100km from Maputo provided an inkling of what was to come. Two stops on the South African side for customs and passports, and no fewer than seven to gain entry into Mozambique.

The road surface progressively deteriorated on the journey northwards from Maputo to Lilongwe via Vilanculos, Beira and Tete. Despite travelling as fast as safely possible, leaving each day at 6am to avoid driving in the dark, our average speed scarcely inched above 60km/h.

At one point, in the 70km between Changara and Guro, south of Tete, only a small strip of road was open for 30km, forcing an informal stop-go arrangement – and the occasional game of chicken – with the fuel, logging and other trucks that dominate the route. Save for the very good road between the port of Beira and Chimoio on the corridor with Zimbabwe, the surface followed a predictable pattern – an okay sector for a few kilometres, followed by disintegration of the road in the dips and around the bridges, and then whole sections where the road, for reasons of age, lack of maintenance, the quality of the original construction, and the extent of rainfall, had simply fallen apart into potholes, which sometimes spanned its entire width.

There were additionally five tolls, costing a total of 220 meticais, including 50 meticais (or $1) for the journey over the Rio Save bridge. The journey over the border to Dedza cost 100 meticais on the Mozambican side for a road pass, and $20 for road tax and $50 for car insurance in Malawi. The woman who removed the bollard at the Malawi border also asked for 4,000 kwacha, or $5.

And then there was the software, human challenge of Sergeant Silvestre and his ilk.

In the 1,833km from Maputo to the Malawian border at Dedza, we encountered 97 police and army roadblocks, being stopped at no fewer than 64 of them. Without fail they asked for water, sometimes food. There were nine speed traps between Maputo and Tete, at which we were stopped twice and forced to pay on-the-spot fines, one for travelling at 66km/h in a 60 zone (I was going 56 according to the GPS), the other for going 82km/h in a 60 zone. With no signs, it’s virtually impossible to know what the speed limit is.

That, one supposes, is the whole idea.

The sergeant pretended to write down our details on a small piece of paper at Save. As he circled the car, continuously tapping on our, by now, rolled-up windows, while his colleagues peered in the back of our Land Cruiser, we pretended to ignore him. Eventually I could take no more, rolled down the window and let rip. He changed tack, rubbing his hand on his stomach while pretending to drink a bottle. A Red Bull, bottle of water and 200 meticais lighter, we were again on our way, smiles all around.

Aggravation aside, such exchanges add costs and complexity to an already fraught journey littered with broken trucks and road accidents, one involving four trucks which we only narrowly avoided.

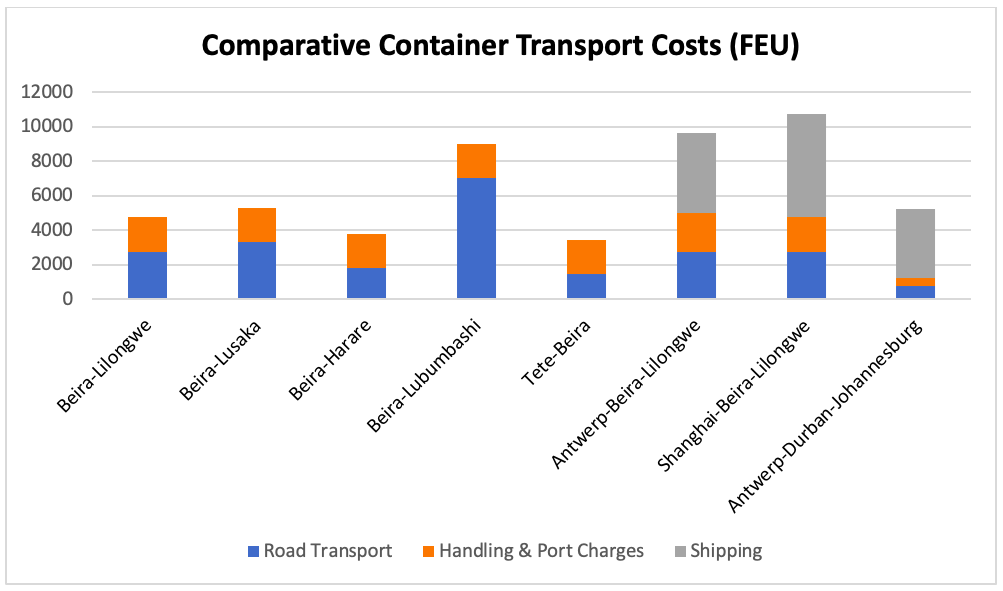

It explains why the cost of moving a (forty-foot – or FEU) container to Lilongwe is around $4,750, including port and handling charges totalling $2,000 – nearly 10 times the cost through Antwerp, for example. The cost of moving a container through Beira and on to Harare is $3,800, Beira-Lusaka is $5,300, and Beira to the Congo a whopping $9,000. The comparative cost of shipping an FEU 10,000km from Shanghai to Beira is $6,000.

The journey reminded us – you have a long time to think over five days of travelling, plus one waiting around for a Covid test result – that Mozambique in 2021 is the chronological equivalent of Singapore in 2011, the East Asian city-state having received independence effectively in 1965 on the dissolution of the Malay Federation. There are differences, of course, not least the extent of the geography and the nature of the respective regions, but it does remind how little progress has been made, of the cost of war, the extent of the carelessness of its political leadership, and of the relative impotence of donors to enable development.

We stopped off in the villages of Mulambo and Mvala, close to the Malawian border post of Dedza. There we met the Mozambique Leaf Tobacco (MLT) “Farmer of the Year”, Atanasio George (45) and his wife, Edita Lorenzo. They had increased their tobacco yield to 1.6 tonnes per hectare, enabling the duo to purchase a cart, build a house, and buy a herd of cattle. MLT was assisting them with maize seed to improve their food security.

The leaf technician, or extension officer, Edison Lazarus, who arrived on his motorcycle with a solar-powered tablet containing information on the 250 farmers on his watch, spoke about new crop possibilities, including honey and vegetables, in the area, which is already known for its fruit and tomato production.

Just 10km away, we stopped to speak to José Charles (45), who farms eight hectares of maize and seven of tobacco, the produce neatly stored in his drying shed. In less than 10 years he has increased his land eightfold, also purchasing cattle, and admitting, with a broad grin, to ownership now of a motorbike.

The tobacco out-grower scheme enables these farmers to access the global economy, and to profit from it. Extending this to other areas demands prying the dead hand of government from controlling – and smothering – such opportunities, and of course identifying and exploiting these new crops where Mozambique, Malawi and other countries can realise their tremendous agricultural potential.

There is no one single answer to the poverty challenge, no one “super crop” or sudden discovery of minerals. To the contrary. Improperly managed and fiscally regulated, such finds can destabilise the fiscus and disincentivise diversification, not least by raising currency values – what is known as “Dutch disease”.

Across the range of economic activities bringing down transport and access costs is the critical element of meeting the development and demographic challenge.

The answer to Mozambique and Malawi’s railway problems lies not in the construction of new, expensive lines, but getting existing links to work properly.

The government should prioritise Access Malawi – an initiative to reduce the premium of transport as a driver of diversification and wealth creation. This should centre on developing rail alternatives to Nacala and Beira, aligning customs systems and procedures across the region as a matter of urgency, simplifying border post procedures and making these easy to follow, improving road safety and maintenance, and instilling a greater sense of regional collaboration and compliance.

Here regional diplomacy is critical. The leaders of both Malawi and Mozambique – and their supporters outside – need to contemplate the contemporary role of borders in Europe when they consider the means to spur regional trade and integration. Today in Europe these are signified by signs that you flash by at 90km/h, or more. In Africa, borders remain places to slow down traffic, to do arbitrage, to extract bribes and “help”, and exact a premium of money, hassle and, above all else, uncertainty.

Absent a solution to the state of the roads, and the frictional costs of the man with a gun and a uniform, the prospects of trading to prosperity remains remote. DM

Greg Mills is with the Brenthurst Foundation. Richard Harper is a logistician. Mike du Toit is a farmer and conservationist. The longer report on which this diagnostic is based can be found here.

Comments

Post a Comment